On 23rd July 1911 the American explorer Hiram Bingham, whilst searching for the “Lost Inca City” of Vilcambamba, entered the plain of Mandor Pampa in the Urubamba river valley and decided to stop and set up camp for the night. A farmer who lived nearby approached the camp to enquire why they didn’t want to stay with him in his tiny, thatched hut.

After a long conversation between the farmer, Melchor Arteaga, and an armed escort of Bingham’s who also acted as an interpreter for the Quechua-speaking locals, Sergeant Carrasco of the Peruvian army, Arteaga learnt of Bingham’s search for old ruins in the area. He mentioned that he knew of some excellent ruins very close-by, at the top of the ridge between the Huayna Picchu and Machu Picchu mountains.

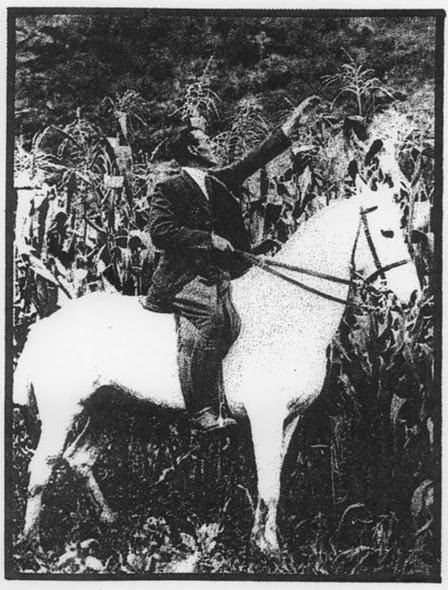

Bingham’s party didn’t react too enthusiastically to this information thinking that the ruins would be of little interest and the majority of them decided to stay in camp the following morning whilst Bingham and Carrasco went off to explore led by Arteaga who was only persuaded to guide them after the payment of one sol. After crossing a rickety old wooden bridge over the very fast flowing Urubamba river, with Bingham making his way across extremely carefully on his hands and knees, they struggled up a steep slope thick with jungle using their fingernails and carefully positioned ladders to drag themselves up almost sheer cliffs in places.

At the same time they were constantly on the lookout for any of the many poisonous snakes that inhabited the surrounding vegetation.

Shortly after noon they had reached a height of around 2000 feet above the river and, exhausted, thirsty and soaking wet from the high humidity, found themselves at a tiny grass-covered hut.

The two farmers who lived in the hut, Melquiades Richarte and Anacleto Alvarez, welcomed their grateful visitors with a meal of sweet potatoes and gourds filled with refreshing water. The farmers explained that there were numerous terraces in the vicinity upon which they could grow their crops and that they were also nicely hidden away from any undesirable visitors on the look-out for taxes or volunteers for the army.

After resting for some time Bingham and Carrasco left the hut along with Richarte’s eleven year old son Pablo, who acted as a guide. Bingham still wasn’t expecting to find anything other than a few overgrown ruins of stone houses but soon he found himself walking past walls made from some of the finest quality stonework he had ever seen. Pablo, the young guide, then took Bingham into an underground chamber lined with beautiful cut stones.

Above this chamber was a semi-circular building, similar to the Temple of the Sun in Cusco, again supremely constructed. Bingham was by now becoming more and more excited at what he was seeing and the fantastic discoveries just kept on coming. He was now certain he had finally found the great Inca city of Vilcapampa.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that the explorer Gene Savoy found the real location of the city of Vilcabamba at Espiritu Pampa, about 40 miles to the NW of Machu Picchu. Hiram Bingham had explored this area in his first visit to Peru in 1909 and had discovered a number of small ruins close to where Vilcabamba would eventually be revealed but thought them to be insignificant and thus ruled them out as a possible site for Vilcabamba.

Once he had visited Machu Picchu its magnificence suggested to Bingham that this must in fact be “The Lost City of the Incas”. Savoy’s discovery and later research by the likes of Vincent Lee and John Hemming showed Bingham to be incorrect. What then, exactly, was Machu Picchu?

The Historical Ownership of Machu Picchu

There has been much conjecture over the origin and function of Machu Picchu since Bingham announced its existence to an amazed world in 1911. The most probable scenario is that Machu Picchu was constructed in the early 15th century by the Inca emperor Pachacuti and served as a kind of summer holiday retreat for him.

The Historical Ownership of Machu Picchu

There has been much conjecture over the origin and function of Machu Picchu since Bingham announced its existence to an amazed world in 1911. The most probable scenario is that Machu Picchu was constructed in the early 15th century by the Inca emperor Pachacuti and served as a kind of summer holiday retreat for him.

During his residence there the population living there may have been a maximum of around 1000 with around 200-300 “staff” taking care of the site during the off-season. Many of the buildings at Machu Picchu would have been residential but there were also other facilities for carrying out religious ceremonies, various industries (stone-masonry, tool-making, pottery, etc.) making astronomical observations and food preparation. The food needed to feed all the residents was grown on the numerous large agricultural terraces found nearby. These terraces were still being used by local farmers to grow crops when Bingham first visited in 1911.

The mountain of Machu Picchu had been known about long before Hiram Bingham’s discovery but, apart from a few local farmers and local historians, no one was truly aware of what secrets were waiting to be found upon its high peak until the late 19th century. After the abandonment of the city in the late 15th century upon the death of the Inca emperor Pachacuti (whose estate Machu Picchu belonged to) the site, of high agricultural interest, was using only for farming and was inhabited only by those who farmed on the surrounding land.

The mountain of Machu Picchu had been known about long before Hiram Bingham’s discovery but, apart from a few local farmers and local historians, no one was truly aware of what secrets were waiting to be found upon its high peak until the late 19th century. After the abandonment of the city in the late 15th century upon the death of the Inca emperor Pachacuti (whose estate Machu Picchu belonged to) the site, of high agricultural interest, was using only for farming and was inhabited only by those who farmed on the surrounding land.

The estate of which Machu Picchu was part still had to be a tribute to the Spanish via the town of Ollantaytambo despite being the city now being abandoned and therefore still employed an official (known as a “curaca”) to carry out the necessary administrative tasks. In 1568 the last known curaca of the city was Juan Macora who, due to his forename of “Juan”, must have been baptised as a Christian and possibly subject to some Spanish influence.

So it can be assumed that the Spanish were at least aware of the existence of the Machu Picchu district without being aware of it’s historic and cultural significance. As long as they continued to receive the correct tribute they would have had no need to actually visit the district. Numerous documents of the time refer to the site by various different names “Piocho”, “Picho”, “Piccho”, “Picchu” but that may just be due to confusion over the exact spelling by officials unfamiliar with the Quechua language.

In May 1565 the Spanish corregidor Diego Rodriguez de Figueroa, was sent to liaise with the rebel Inca leader Titu Casi at the bridge of Chuquichaca. In the account of his journey there he mentioned that the Inca road which crossed the Vilcabamba river led to the settlements of “Sapamarca, Tambo and Picho”. “Tambo” refers to Ollantaytambo whereas “Picho” is though to refer to Machu Picchu.

In 1614 the land around Machu Picchu had apparently passed into the ownership of the local Canaris tribe, led by their cacique (chief) Don Francisco Poma Gualpa. In 1657 the area was leased temporarily by a group of Augustinian friars who used the land for farming but had no knowledge of the ruins which by then had been abandoned for over 150 years and would have already have been extensively covered by the surrounding jungle.

In 1614 the land around Machu Picchu had apparently passed into the ownership of the local Canaris tribe, led by their cacique (chief) Don Francisco Poma Gualpa. In 1657 the area was leased temporarily by a group of Augustinian friars who used the land for farming but had no knowledge of the ruins which by then had been abandoned for over 150 years and would have already have been extensively covered by the surrounding jungle.

The site containing Machu Picchu and its neighbouring mountain of Huayna Picchu (described as a land without tools, cattle or houses) was sold by Manuela Almirón y Villegas to the brothers Pedro and Antonio Ochoa for 350 pesos in 1776. Six years later the Ochoa brothers, represented by the uncle who was a local bishop, sold on the land for the sum to 450 pesos to Commander Marcos Antonio de la Camara y Escuerdo, the Spanish mayor of the Urabamba valley district.

The Cutija hacienda, which contains the site of Machu Picchu, may then have changed numerously times over a short period of time before being donated to an order of monks who held the property for a number of decades before leaving the region some time in the early 19th century. The hacienda then became the property of the Nadal family, from Cusco.

In 1905 the Nadals sold the estate to Mariano Ignacio Ferro who still owned it when Hiram Bingham arrived in 1911 and offered some assistance to the American explorer. Mariano Ignacio Ferro died in 1934 the deeds of the land passed to his daughter Tomasa and her husband Emilio Abrill Vizcarra, a lawyer from Cusco who would go on to become major of the city and later a senator. Machu Picchu was then bought by the Zavaleta family in 1944.

In recent years there have been a number of legal wrangles over who actually owns the land upon which the ruins are found. The family of Abrill Vizcarra still claim ownership saying that the Zavaleta family bought only a section of the land contained in their deeds whereas the Zavaletas maintain that they own the whole of the property. Confusing things even more is the fact that the government of Peru declared that they expropriated ownership of the site in 1944 because of the Peruvian that insists that all significant archaeologist sites in the country are property of the nation.

The site was made a historic sanctuary in 1981 and two years later UNESCO gave it the status of a World Heritage site. Despite this, both the Abrill and Zavaleta families insist that they should have received payment from the Peruvian government and are demanding compensation of millions of dollars as well as a share in the income received from the almost one million years to the site every year.

Is 2011 really a Centenary?

There is quite a lot of resentment in Peru about the celebrations for the 100th anniversary of Bingham’s “discovery” which has involved much pomp, visits from major celebrities and spectacular events in the weeks leading up to the anniversary on 24th July. During Bingham’s subsequent visits to Machu Picchu between 1912 and 1915 he unearthed many artefacts, including ornaments, jewellery, tools, musical instruments and bone fragments, which he transported back to Yale University in crates for further examination.

Is 2011 really a Centenary?

There is quite a lot of resentment in Peru about the celebrations for the 100th anniversary of Bingham’s “discovery” which has involved much pomp, visits from major celebrities and spectacular events in the weeks leading up to the anniversary on 24th July. During Bingham’s subsequent visits to Machu Picchu between 1912 and 1915 he unearthed many artefacts, including ornaments, jewellery, tools, musical instruments and bone fragments, which he transported back to Yale University in crates for further examination.

However, he didn’t find a single precious object made from gold or silver as might have been expected at such a prestigious Inca site. One explanation for this is that Machu Picchu had been visited before Bingham and that those visitors had taken away anything of value leaving behind artefacts of archaeological value only. This can also explain how such anachronistic items as horse bones, a peach stone and various steel implements were found at the site by Bingham’s researchers.

It was recently discovered that Yale has more than 40,000 pieces from Machu Picchu in their possession, many of them still in unopened crates. After a legal dispute that has dragged on for many years Yale recently consented to return all of these pieces to Peru and the first batch, containing those of the highest quality, went on display in the Casa Concha museum in Cuzco at the start of July. The rest will follow over the next year or two.

Another major source of dispute is the belief that Bingham didn’t give enough credit to the many Peruvians who helped him to reach the site of Machu Picchu. Right at the top-level the Peruvian president at the time, Augusto Leguia, grant Bingham’s party military escorts along with letters of introduction.

It was recently discovered that Yale has more than 40,000 pieces from Machu Picchu in their possession, many of them still in unopened crates. After a legal dispute that has dragged on for many years Yale recently consented to return all of these pieces to Peru and the first batch, containing those of the highest quality, went on display in the Casa Concha museum in Cuzco at the start of July. The rest will follow over the next year or two.

Another major source of dispute is the belief that Bingham didn’t give enough credit to the many Peruvians who helped him to reach the site of Machu Picchu. Right at the top-level the Peruvian president at the time, Augusto Leguia, grant Bingham’s party military escorts along with letters of introduction.

He was also allowed free passage on trains and free use of telegraphs. He was given much help and information in his quest by various local officials and academics. In January 1911 the newly appointed American-born rector of the University of Cuzco, Alberto Giesecke, went on a fact-finding expedition in the Urubamba valley along with a local landowner, Braulio Polo y la Borda.

They made their way through the valley until they came to a small hut at Mandor Pampa. They asked the farmer who lived there if there were any notable ruins in the vicinity and he replied that there were numerous stone ruins on top of a nearby ridge. As it was the wet season Giesecke and Polo y la Borda decided that it wouldn’t be possible to follow-up the lead at that time and hoped to return later in the year during the dry season.

When Bingham visited Cuzco in July 1911 they visited the University and during a conversation with Giesecke he was told about the ruins close to Mandor Pampa and that he should speak to the farmer who lived there, Melchor Arteaga.

On his expedition to the ruins of Choquequirao in 1909 Bingham’s party included Juan Jose Nunez, the Prefect of the Apurimac region. By July 1911 Nunez was prefect of Cuzco and supplied Bingham with all the help he might need during his search for the ruins of Vilcabamba. This included the Cusquena soldier Sergeant Carrasco who acted as Bingham’s protector and translator.

Then there were those directly involved in Bingham’s visit to Machu Picchu –, the farmers Melchor Arteaga, Melquiades Richarte and Anacleto Alvarez and Richarte’s young son Pablo. Bingham also heard about the ruins from other local residents such as Alberto Duque (who lived on the Santa Ana hacienda close to Mandor Pampa), a Senor Pancorbo, (who owned a plantation in the Vilcabamba valley), and the prefect of the town of Urubamba but paid them little attention.

Last, but not least, is the claim that Bingham wasn’t actually the first man to visit Machu Picchu. It was certainly visited by local Indians over the preceding centuries, for example the farmers Arteaga, Richartes and Alvarez who had been living on the site since 1904 and paid a annual fee of 12 soles for farming rights on the property. During his visit Bingham found evidence of a visit by a group of Peruvians in 1902.

On his expedition to the ruins of Choquequirao in 1909 Bingham’s party included Juan Jose Nunez, the Prefect of the Apurimac region. By July 1911 Nunez was prefect of Cuzco and supplied Bingham with all the help he might need during his search for the ruins of Vilcabamba. This included the Cusquena soldier Sergeant Carrasco who acted as Bingham’s protector and translator.

Then there were those directly involved in Bingham’s visit to Machu Picchu –, the farmers Melchor Arteaga, Melquiades Richarte and Anacleto Alvarez and Richarte’s young son Pablo. Bingham also heard about the ruins from other local residents such as Alberto Duque (who lived on the Santa Ana hacienda close to Mandor Pampa), a Senor Pancorbo, (who owned a plantation in the Vilcabamba valley), and the prefect of the town of Urubamba but paid them little attention.

Last, but not least, is the claim that Bingham wasn’t actually the first man to visit Machu Picchu. It was certainly visited by local Indians over the preceding centuries, for example the farmers Arteaga, Richartes and Alvarez who had been living on the site since 1904 and paid a annual fee of 12 soles for farming rights on the property. During his visit Bingham found evidence of a visit by a group of Peruvians in 1902.

He may not even have been the first non-Peruvian to reach the site as there is some evidence that a German, Augusto Berns, may well have been there in the 1860s and an Englishman Thomas Payne possibly visited in 1906. Many explorers had come very close to stumbling across the ruins during various expeditions in the 19th century. The exploration of the Machu Picchu region pre-Bingham will be explained in more detail later on in this article.

Bingham was familiar with much of the literature written about these previous visits and may even have carried a map of the area, produced by the Peruvian explorer Antonio Raimondi, which clearly displayed the name of Machu Picchu upon it. However, he had a tendency to distort or hide any information found in this literature that was contradictory to his own viewpoint.

Bingham was familiar with much of the literature written about these previous visits and may even have carried a map of the area, produced by the Peruvian explorer Antonio Raimondi, which clearly displayed the name of Machu Picchu upon it. However, he had a tendency to distort or hide any information found in this literature that was contradictory to his own viewpoint.

Furthermore he has been accused of downplaying his knowledge of this literature and also the amount of help he received from various individuals so as to make his tale of discovery sound more thrilling and triumphant. For this reason Bingham’s achievement is nowadays often re-branded as a “re-discovery” or referred to as the “scientific discovery” of Machu Picchu. Bingham certainly was the first person to bring the existence of Machu Picchu to the attention of the outside world, to recognise the scientific and archaeological significance of the site and to begin to finally rescue it from the stranglehold the surrounding jungle had had over the ruins for 500 years.

Many of Bingham’s speculations about Machu Picchu subsequently turned out to be incorrect but nevertheless he paved the way for future archaeologists and historians to carry out their own findings.

Exploration of Machu Picchu and it’s surroundings

Exploration of Machu Picchu and it’s surroundings

pre-Bingham

It wasn’t until the 19th century that foreigners first started to examine the region. But most of them were attempting to find other historical sites such as the last Inca capital of Vilcabamba or the nearby Inca city of Choquequirao and had no knowledge of the existence of the city of Machu Picchu. Others came to the area in order to seek their fortunes in natural resources such as rubber, timber and minerals.

In 1834 the French explorer Eugene de Sartiges, along with the Peruvians Jose Maria Tejada and Marcelino Leon, visited the ruins of Choqquequirau. His route started at the village of Mollepata before passing between Mount Soray and Mount Salancay and ended up at the hamlet of Huadquina in the Santa Teresa valley, only a few miles of Machu Picchu, then still unknown to the outside world.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that foreigners first started to examine the region. But most of them were attempting to find other historical sites such as the last Inca capital of Vilcabamba or the nearby Inca city of Choquequirao and had no knowledge of the existence of the city of Machu Picchu. Others came to the area in order to seek their fortunes in natural resources such as rubber, timber and minerals.

In 1834 the French explorer Eugene de Sartiges, along with the Peruvians Jose Maria Tejada and Marcelino Leon, visited the ruins of Choqquequirau. His route started at the village of Mollepata before passing between Mount Soray and Mount Salancay and ended up at the hamlet of Huadquina in the Santa Teresa valley, only a few miles of Machu Picchu, then still unknown to the outside world.

He actually named the mountain of a map included in his report on the journey a number of years later in 1891 but made no mention of its ruins. Raimondi’s map is of one of a number of maps that were produced prior to Hiram Bingham’s visit which show either Machu Picchu or its surroundings.

In 1868 the Peruvian government hired the Swedish-born American engineer John Nystrom to chart a path linking Cuzco to with the Santa Ana valley. This route, which ran alongside the Urubamba river shows the source of a hot spring (“Aguas Calientes” in Spanish). However, Nystrom’s map makes no mention of Machu Picchu which was located just across the river.

In 1904 the archaeologist Carlos Cisneros published The Atlas of Peru which contained a survey of all the known archaeological sites in Peru. In the section on the Department of Cuzco he mentions that there are a number of Inca villages in the Urubamba valley where there have still been no excavations, one of these being “Huaina-Piccho”.

In October 1910 the British historian Sir Clements Markham published in a paper entitled “The Land of the Incas” in the Royal Geographical Journal. Sir Clements, who had been president of the Royal Geographic Society. As an attachment to this paper Clements had produced a map showing southern Peru and northern Bolivia upon which is marked the location of “Cerro Machu Picchu”.

Again, this refers only to the mountain and no reference to the presence of any ruins is noted in either the map or the accompanying text. Hiram Bingham was said to have carried a copy of this map with him during his expedition the following year.

For many years it was believed that the first map to mention the names of the mountains of Machu Picchu and Huayna Picchu was that drawn by the French explorer Charles Wiener in 1875, although he labelled the mountains the wrong way round. The previous year he had travelled to the Urubamba valley and once he had reached the town of Ollantaytambo he received information from the locals that fine Inca ruins lay further up the valley at a place called “Huaina-Picchu or Matcho-Picchu.”

For many years it was believed that the first map to mention the names of the mountains of Machu Picchu and Huayna Picchu was that drawn by the French explorer Charles Wiener in 1875, although he labelled the mountains the wrong way round. The previous year he had travelled to the Urubamba valley and once he had reached the town of Ollantaytambo he received information from the locals that fine Inca ruins lay further up the valley at a place called “Huaina-Picchu or Matcho-Picchu.”

Upon hearing this he left to try to find these ruins by travelling, via a pretty circuitous route due to their being no other possible path at that time, up through the Panticalla pass and the Lucumayo valley to reach the same Choquechaca bridge that Antonio Raimondi had visited 16 years previously. From Choquechaca Wiener then decided to head further down-river, towards the plantation of Santa Ana rather than up-river which would have taken him towards Machu Picchu because of the difficulties heading in that directions would bring.

In 1989 the American historian and explorer Paolo Greer discovered a map from 1874 which also showed the location and name of the Machu Picchu mountain, but again without any mention of the ruins. This map had been created by the German geologist Herman Gohring who had been part of an expedition in 1872 led by an explorer from Cusco by the name of Baltasar de la Torre. De la Torre’s hoped to find a route from Cusco, via the town of Paucartambo, to the jungles of Madre de Dios. He managed to reach the jungle but once there came into contact with one of the local tribes who, with 35 of their arrows, soon put an end to de la Torre’s journey, and to his life. Herman Gohring, who hoped to find possible locations for gold-mines, was also part of de la Torre’s party but he managed to survive the attack and in 1877 published an account of the trip, Informe Supremo de Paucartambo, in which his 1874 map appeared. In this account he mentions “the forts of Chuquillusca, Torontoy and Picchu” in the region close to Ollantaytambo, the latter clearly referring to Machu Picchu.

In 1978 Paolo Greer had also discovered a map showing the location of gold mines in the Urubamba valley drawn by the American Harry “Poker” Singer in the 1870s. Singer was a chemist, miner and surveyor who had spent six years studying at Gottingen University in Germany before taking part in the California gold rush of 1849. As well as the gold mines Singer’s map also showed a road leading up to Mandor Pampa and the location of a saw-mill close to the current site of the small town of Aguas Calientes, from where the thousands of modern day tourists make their way up to the ruins of Machu Picchu.

This saw mill was the property of Singer’s business partner, Augusto R. Berns. In 1867 the German engineer and adventurer bought the hacienda of Torontoy, comprising of 25 square kilometres of land on the northern side of the Urubamba river, from a Senor Angulo of Cuzco (who also happened to be the father of his wife Carmen). The estate included the ruined Inca fortress of Torontoy as well as a farmstead at San Antonio and was just across the river from Machu Picchu.

In 1989 the American historian and explorer Paolo Greer discovered a map from 1874 which also showed the location and name of the Machu Picchu mountain, but again without any mention of the ruins. This map had been created by the German geologist Herman Gohring who had been part of an expedition in 1872 led by an explorer from Cusco by the name of Baltasar de la Torre. De la Torre’s hoped to find a route from Cusco, via the town of Paucartambo, to the jungles of Madre de Dios. He managed to reach the jungle but once there came into contact with one of the local tribes who, with 35 of their arrows, soon put an end to de la Torre’s journey, and to his life. Herman Gohring, who hoped to find possible locations for gold-mines, was also part of de la Torre’s party but he managed to survive the attack and in 1877 published an account of the trip, Informe Supremo de Paucartambo, in which his 1874 map appeared. In this account he mentions “the forts of Chuquillusca, Torontoy and Picchu” in the region close to Ollantaytambo, the latter clearly referring to Machu Picchu.

This saw mill was the property of Singer’s business partner, Augusto R. Berns. In 1867 the German engineer and adventurer bought the hacienda of Torontoy, comprising of 25 square kilometres of land on the northern side of the Urubamba river, from a Senor Angulo of Cuzco (who also happened to be the father of his wife Carmen). The estate included the ruined Inca fortress of Torontoy as well as a farmstead at San Antonio and was just across the river from Machu Picchu.

Initially Berns hoped to use the land to produce timber for use as sleepers for the Southern Peru railroad. To this end he built the large saw-mill shown on Harry Singer’s map, as described above. When Hiram Bingham reached that location during his expedition in July 1911 he named it as “La Maquina” (“The Machine”) due to the presence of some large iron wheels that had been left to rust. Bingham speculated that they were part of a machine used to process sugar cane but they were actually parts of Bern’s saw-mill. He had abandoned the saw-mill in 1881 when he changed his business interest from timber to more precious materials.

Berns intended to explore the many old mines and Inca ruins in the region and selling whatever treasures he might find. In 1887 he created a new business, “Compañía Anónima Exploradora de las Huacas del Inca”, (“Huacas” being objects that were sacred to the Incas) in order to carry out this task and was given permission by the Peruvian government to do so. He issued a prospectus outlining his plans and hoped that it wouldattract investors into buying up shares in the company.

Berns intended to explore the many old mines and Inca ruins in the region and selling whatever treasures he might find. In 1887 he created a new business, “Compañía Anónima Exploradora de las Huacas del Inca”, (“Huacas” being objects that were sacred to the Incas) in order to carry out this task and was given permission by the Peruvian government to do so. He issued a prospectus outlining his plans and hoped that it wouldattract investors into buying up shares in the company.

As part of this prospectus he produced a map of the area showing the possible locations of gold and silver mines and Inca ruins. This map was probably based on the map that Harry Singer had produced when he had prospected the region for Berns in the 1870s. Just across the river from where he had marked the location of his saw-mill Berns had written “Point Huaca Inca” but also pointed out that this side of the river was “inaccessible”.

There is no real evidence that Berns actually set foot on Machu Picchu but from his map it seems clear that he was aware of its existence. He had lived in the area for many years and must have heard about the ruins from other landowners and inhabitants. And if he was interested in ransacking ruins in order to find their hidden treasures surely he would have investigated the site. This may well explain the lack of valuable items found at Machu Picchu by Bingham and his party.

There is no real evidence that Berns actually set foot on Machu Picchu but from his map it seems clear that he was aware of its existence. He had lived in the area for many years and must have heard about the ruins from other landowners and inhabitants. And if he was interested in ransacking ruins in order to find their hidden treasures surely he would have investigated the site. This may well explain the lack of valuable items found at Machu Picchu by Bingham and his party.

There is one person for which there is definite proof thathe visited Machu Picchu before Hiram Bingham. This is the Peruvian Agustin Lizárraga, a muleteer from Cuzco who , in charcoal, wrote his surname and the year 1902 onto a rock at Machu Picchu where it was later found by Bingham.

Lizárraga was accompanied on his journey, on 14th July 1902 (almost ten years to the day before Bingham’s visit) by Gabino Sanchez (from the Caicay district) and Enrique Palma. All three of them were agricultural workers on the Colpani estate in the district of San Miguel and also had the task of taking care of all the bridges over the Urubamba river between Cuzco and Quillabamba.

Lizárraga was born in the town of Mollapata and had lived in the nearby valley for over thirty years but, apart from writing his name on the rock, made no mention of his visit and as he was only a simple peasant and not a historian or explorer no-one would have probably taken much notice if he had done so. His party was only interested in Machu Picchu for the treasures that may have been hidden beneath the vegetation.

Lizárraga may even have returned to Machu Picchu in 1904 whilst acting as a guide for a tour party of 12 which apparently included the daughter of the owner of the Colpani estate, Maria Ochoa-Manga who may well have been one of the first tourists to ever visit the site. Lizárraga also claimed to have guided a local aristocrat, Don Señor Luis Bejar Ugarte to the ruins in 1894 which would have been the earliest known visit to the locale if true.

Lizárraga may even have returned to Machu Picchu in 1904 whilst acting as a guide for a tour party of 12 which apparently included the daughter of the owner of the Colpani estate, Maria Ochoa-Manga who may well have been one of the first tourists to ever visit the site. Lizárraga also claimed to have guided a local aristocrat, Don Señor Luis Bejar Ugarte to the ruins in 1894 which would have been the earliest known visit to the locale if true.

In February 1912, shortly after meeting Bingham, Lizárraga fell into the Vilcanota river whilst attempting to make a crossing and drowned. In 1915 during Bingham’s 2nd visit to Machu Picchu to carry out excavations Lizárraga’s charcoal scrawl was erased. Whether this was accidental or purposeful, in order to try to hide evidence of an earlier visitor, is unclear.

Other possible visitors to Machu Picchu before Bingham were the British missionaries Thomas Payne and Stewart McNairn in 1906 and the Germans Jorge von Hassel and Carl Haenel in 1910. Thomas Payne was an English Baptist who lived in Peru between 1903 and 1952. Shortly after arriving in Peru in 1903 Payne was living on a missionary farm near Cuzco where one day he met an American gold-mine prospector called Franklin who told him that whilst travelling down an old Inca road he spotted some old ruins at the top of a nearby mountain but hadn’t had time to explore them.

Other possible visitors to Machu Picchu before Bingham were the British missionaries Thomas Payne and Stewart McNairn in 1906 and the Germans Jorge von Hassel and Carl Haenel in 1910. Thomas Payne was an English Baptist who lived in Peru between 1903 and 1952. Shortly after arriving in Peru in 1903 Payne was living on a missionary farm near Cuzco where one day he met an American gold-mine prospector called Franklin who told him that whilst travelling down an old Inca road he spotted some old ruins at the top of a nearby mountain but hadn’t had time to explore them.

Payne was too busy to follow this information up at the time but three years later, Stuart McNairn, a Scottish Presbyterian, came to live at the farm and Payne asked him if he wished to join him on an expedition to the ruins. They apparently reached the ruins, spent the night there and descended the following day.

McNairn would later tell of this trip to a mining engineer, and fellow Scot, named Stapleton. In 1909 this Stapleton then apparently passed on this story to Hiram Bingham and that Bingham should contact Payne for more information. The following year it is said the Bingham visited Payne’s farm when he was told about the location of the ruins and how to reach them.

McNairn would later tell of this trip to a mining engineer, and fellow Scot, named Stapleton. In 1909 this Stapleton then apparently passed on this story to Hiram Bingham and that Bingham should contact Payne for more information. The following year it is said the Bingham visited Payne’s farm when he was told about the location of the ruins and how to reach them.

There is no record of Stapleton or Payne to be found anywhere within Bingham’s documentation but as has been said previously, Bingham was quite capable of suppressing any information that might take any credit away from himself for the discovery of Machu Picchu. However, there is also no real evidence to be found elsewhere other than a few stories told by some of Payne’s descendents and colleagues.

In September 1916, five years after reports of Bingham’s expedition to Machu Picchu had been published, the German engineer Carl Haenel wrote a letter to a Berlin newspaper that claimed that the explorer JM von Hassel, his fellow countryman, had actually beaten Bingham to the ruins by a year. His letter went on to claim that it was only the outbreak of the First World War that prevented a major German expedition to the Inca city, which he referred to as “Tampu Tocco”.

Hanael also claimed that von Hassel had written up an account of this expedition in as part of a paper entitled “Vias de la Montana” which was published in the northern Peruvian jungle city of Iquitos in 1909.

This paper showed the results of a survey von Hassel had carried out with the Peruvian Water Board in the early 20th century, on behalf of the government, to find possible rail, road and water routes within the Cuzco region which might be used to open up the area to commercial development. However, despite Haenel’s claims von Hassel’s paper has no mention of the discovery of any ruins and makes only vague references to locations that might have any semblance to Machu Picchu or its surroundings.

Nevertheless in 1904 he did produce a map of the region as a result of an earlier survey for the Peruvian water board upon which “Cerro Machu Pichu” was marked...OP+